The Biden Administration’s actions in the past week demonstrate a truly remarkable bipolarity with regard to empowering consumers.

Yesterday, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) issued sweeping data portability rules for banks and fintechs. Known as “open banking,” the requirements allow consumers to have their banking data – transaction history, interest rates and loan information – transferred seamlessly to competing services. The rules are the culmination of a multi-year commitment by the Democratic party to support customer choice, prevent “lock-in,” and fuel competition on price and service quality.

But last Friday in another part of the Biden Administration, the Department of Energy (DOE) dismissed data portability requirements entirely for $592 million in grants to electric utilities.

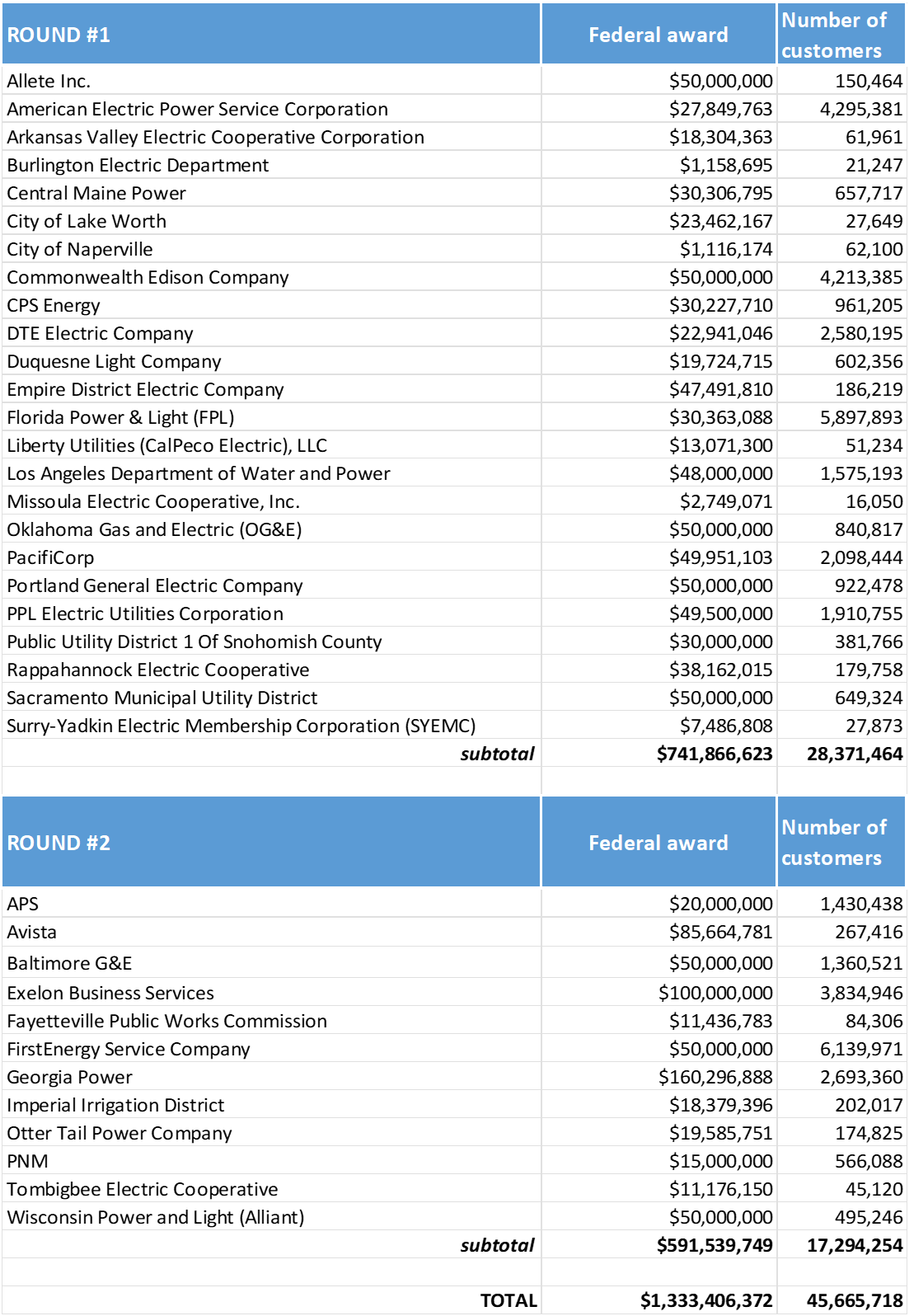

So, while millions of adults will be able to better manage their banking fees and interest expenses, some 45.7 million electric customers – the number of households and businesses touched by these particular DOE grants – will be deprived of similar benefits with regard to their utility bills.

Utilities that won't provide data portability, despite receiving taxpayer funds in 2024. Note: This list is limited to “Smart Grid Grants” and excludes (i) non-utility award recipients and (ii) utilities that offer Green Button Connect, such as National Grid, Consumers Energy and Southern California Edison. Exelon’s number of customers subtracts BG&E/ComEd to prevent double-counting.

Why the fickleness? What explains the Biden Administration’s conflicting positions with regard to competition that reduces prices for consumers? On the surface, it seems like a government that ostensibly supports energy innovation would offer some gesture of philosophical consistency in its policies. Instead, we have a reversal. What’s going on?

Let’s address the most obvious rationale first. “But banking is totally different than electricity!” several colleagues have told me. In other words, no one should expect consistent policies in different sectors of the economy. The products, markets, and regulatory constructs are entirely separate, and so a government’s performance should be judged individually within each domain.

I am unpersuaded by this argument for several reasons. First, the Biden Administration is pursuing data portability and interoperability requirements in numerous disparate sectors such as healthcare, social media, online search, digital wallets and debit transactions. Together, these are trillion-dollar markets that would appear to share little in common. And yet the administration is prosecuting the case for consumer control over their data anyway, unburdened by sector-specific idiosyncrasies.

The rejoinder I hear next is “but electricity is special because the Federal Power Act limits federal authority over electricity to interstate transmission only.” But that’s only partially true; the FPA specifies FERC’s jurisdiction, not DOE’s. DOE has authority over appliance efficiency standards, and since 2007 it has established an array of smart grid and interoperability standards that are decidedly, well, sub-federal in scope. (In fact, in 2023, DOE said it would require utility grant recipients to offer data portability, only to retract its stated requirement – indicating that DOE believed as recently as last year that it does have this authority.)

As former NY PSC chair Audrey Zibelman reminded me recently, the feds offered money to states in the 1970s in order to build the interstate highway system, but there was a catch: The states had to enact seat-belt laws if they didn’t already have them. The “power of the purse” is federalism’s Swiss cheese: Sure, states can self-govern, but they might have to decline large federal funding opportunities in the process.

In my view, based on current and historic examples, the legal objections to DOE’s authority can be overcome. DOE does have the authority to withhold grants to utilities that do not follow its standards. The real question is: Why won’t they use that authority?

I think there are two reasons. First, there is a narrative among energy policymakers in Washington, D.C. that smart meters are like iPods: They are the tech-sensation of yesteryear, no longer worthy of discussion. Why would we waste limited government resources studying settled issues? Since 2006, FERC has issued annual reports on advanced metering and demand response, but these reports are viewed as boring and obsolete given that some 75% of the country now has a smart meter on their home or business. Similarly, DOE has turned the page and simply assumes that smart meters are working properly (despite mounting evidence of market failures).

Second is an aversion to upsetting utilities, particularly the more monopolistic ones that have opposed data portability for years. Electric utilities are supposed to be our allies in decarbonizing the economy. You wouldn’t want to cross a friend, would you? This posture is cowardly, yes, but it’s also antiquated. Amid load growth and rapidly increasing transmission and distribution costs, data portability puts much-needed downward pressure on electric rates by enabling demand response and virtual power plants. True, some utilities may dislike the diminution of their competitive position that data portability might represent. But who cares about monopolies fretting over their “market positioning” (yes, I’m aware of the irony) when we can substantially decrease electric rates?

DOE should look to the future, not the past. There was a time when AT&T opposed telephone number portability – Ma Bell wanted to lock you in to their network and undermine competition for local telephone service. While DOE is, metaphorically speaking, supporting AT&T’s landline business, the rest of the Biden Administration is restructuring markets around tenets of competition and consumer choice. It’s time for DOE to join them.

Update 10/23/2024: The table was updated to reflect accurate meter counts and to exclude SCE, which already offers Green Button Connect.