Klaar De Schepper of Flux Tailor co-authored this post.

Mission:data spends a lot of time working with policymakers on the customer authorization process for sharing energy data with third party energy management companies. We wrote a paper about it last year, and practically all of Mission:data’s regulatory filings discuss it. While technical topics such as XML are involved, the most important issue is not technical at all. Rather, it’s about consent: In online transactions, how can we make sure that customers know what they’re doing? Given recent events, we thought it valuable to analyze the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica incident, and compare and contrast it with transactions involving energy data.

First, the background. Facebook has been in the news for the alleged misuse of 87 million Americans’ data by the Trump campaign-aligned data analytics company called Cambridge Analytica. Back in 2013, a professor named Aleksandr Kogan from the University of Cambridge created a Facebook app called “thisismydigitallife” and paid users $1-$2 to complete the app’s psychological surveys. Some 270,000 people used the app initially, but its data-gathering capability grew substantially thanks to Facebook’s developer API which, at the time, allowed the harvesting of data from the user’s friends as well as just the user. When the press discovered that the resulting personal data of 87 million people was purchased by Cambridge Analytica, a media firestorm ensued.

To Breach or Not To Breach

The fact that personal information from a Facebook app was sold to another entity is not in and of itself an indicator of wrongdoing. After all, personal information is exchanged and traded under entirely legal circumstances every day among businesses large and small. (That’s in contrast to energy data, the sale of which is prohibited by many states.) As one digital marketer commented, “We’ve been doing this for years.” From a legal perspective, the real question about Facebook’s or Cambridge Analytica’s liability is not whether data were sold, but whether the 270,000 users of the app knowingly agreed to have their data shared with other parties. If so, then it would be very difficult to argue that these users were “duped.”

Indeed, Facebook’s initial response to the news stories on March 17 noted that users chose to share their data with thisismydigitallife:

This tweet was disparaged as being “tone-deaf,” but Facebook has a point that has been lost in subsequent media coverage: the key issue is whether users were told that their data could be harvested and traded to other entities. If users were sufficiently informed, then it may be inappropriate to seek remedies from Facebook or thisismydigitallife. From a contractual standpoint, no violation would have occurred if users were sufficiently informed and decided to use the app anyway. (Note: we have yet to see thisismydigitallife’s privacy policy and the permissions it sought from users. Therefore, it’s premature to conclude that a contract with users was violated.)

Newspapers such as The Guardian used the word “breach” in their headlines. But that word is most likely inappropriate in this case, given that no unauthorized access to computer systems occurred, at least according to the latest news reports. Even if users did consent to thisismydigitallife sharing their data with third parties, it would be hard to call the transaction between thisismydigitallife and Cambridge Analytica a “breach,” since the exchange was voluntarily undertaken by both parties. (For more on this topic, listen to Ben Thompson’s excellent podcast, Exponent, on the troublingly imprecise use of language in news headlines concerning Facebook.)

Source: The Guardian, March 17th, 2018

But let’s put aside the definition of “breach” and instead return to the legal issues. Like it or not, much of digital privacy law in the U.S. derives from the terms and conditions on a website or app. States like California require website operators to publish privacy terms. The Federal Trade Commission can sue companies if consumers are deceived by a firm saying one thing in their terms while the firm does another. This is certaintly true in the energy industry: Energy management companies who are signatories to DataGuard face potential FTC investigations if they mislead consumers in this way.

Nevertheless, the fact that language supporting data-sharing might have been buried in thisismydigitallife’s detailed “terms of service” (or that users were informed by notifications of privacy changes over time) does little to placate outraged members of the public. And, to some extent, the outraged have a point: it isn’t reasonable to expect the average person to read and understand every term associated with every website they visit. Doing so would require hours of painstaking analysis for even the most mundane parts of modern life such as making an online restaurant reservation or buying concert tickets. Terms and conditions, this argument goes, are essentially meaningless.

On the other hand, how Facebook and third party apps use your personal information requires disclosure in some form for its bargain with users to be consensual. Users must be presented with something to see if personal information is exchanged for a service of some kind. If all terms of service are meaningless, as some might profess, then users aren’t empowered to make intelligent choices, and companies’ abilities to freely enter into contracts with users, a key tenet of commerce, is compromised. Dismissing altogether the text of “I agree” statements is troublesome because it eliminates users’ agency and decision-making abilities altogether, discarding long-standing bodies of law concerning contracts in the process.

The solution to this dilemma -- that website terms and conditions cannot be meaningless, nor can they be treated as Gospel, with all their inscrutable legalese -- lies in the elusive idea of “informed consent.” Users should be sufficiently informed of how their data will be used before a transaction occurs. If a user fully understands the bargain, then sharing one’s data is a choice he or she should be free to make. In principle, it sounds great; who wouldn’t want to be informed?

But in practice, it is extremely challenging to specify in law or regulation how informed consent should be obtained in a manner that simultaneously satisfies app-makers, users and privacy advocates. Consider the vast difference in user experiences between a desktop computer and a smart watch; clearly, simple icons will have more informative effects on users when shown on a smart watch as compared with lengthy written terms and conditions, whereas greater reliance on text (but with some icons) may be appropriate for a desktop computer. Specifying the consent process in law in the hopes of fully informing users is highly dependent on the digital context. Today’s laws, if they were written, will quickly show their age as technology changes.

Iconography on Android helps users understand app permissions.

Many regulators have attempted to find a solution by articulating abstract principles of informed consent. For example, one principle from the Federal Trade Commission is to “disclose key information clearly and conspicuously”. In the European Union, a new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will go into effect on May 25th, requiring adherence to a similar set of principles. The legislation will apply across industries. Article 12 specifies that information relating to data processing should be provided to “data subjects” in “a concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language.”

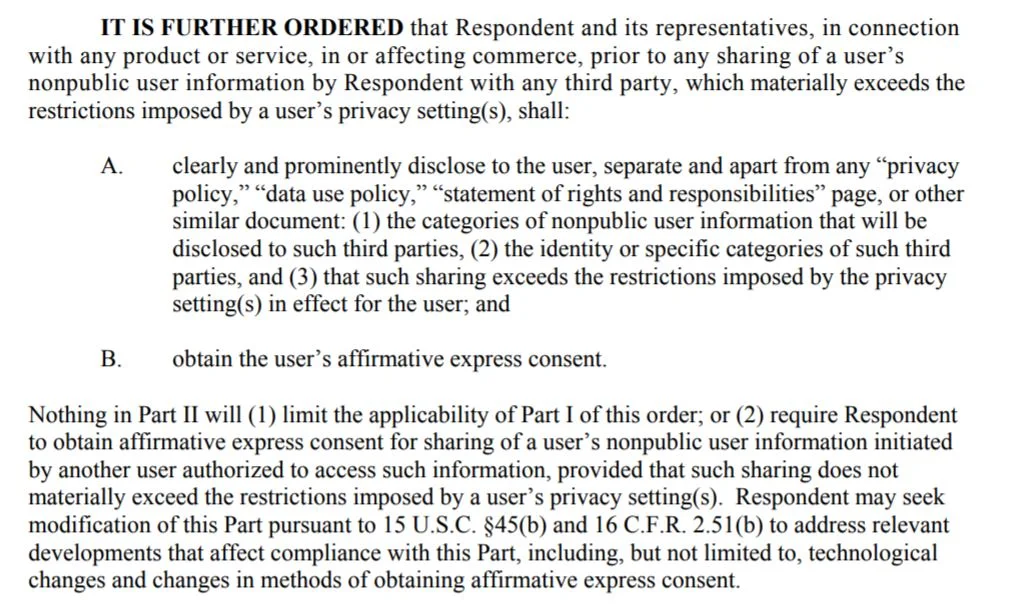

What is informed consent? The above excerpt is from a 2012 order from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which requires Facebook to obtain “affirmative express consent,” whatever that means. We don’t envy the Facebook product manager charged with compliance.

Unfortunately, what is clear and plain is, ultimately, in the eye of the beholder. And herein lies another dilemma: If prescribing the details of consent in law is unworkable due to rapid technological change, then the result is even worse: abstract principles of digital consent are litigated in the courts, creating even more unmanageable and unmalleable requirements written by judges. Such is already happening in Europe. A German court ruled in February, before the Cambridge Analytica news broke, that Facebook had broken the law by not securing consumers’ informed consent. Throughout history, courts have been helpful in applying abstract principles to specific circumstances, but in this case, it could hurt more than it helps. If society’s objective is to maximize informativeness among dynamic digital interactions, then prescribing solutions in legislation appears preferable over the alternative, which is the courts throwing darts in a darkened room at an elusive target.

Perhaps the most unsettling part of the Facebook story is that even if a user granted informed consent to access her data, she couldn’t have provided consent for her friends’ data, too. Unfortunately, access to one’s friends’ data was granted by default (though it could be changed in privacy settings). Here is where the overlap between your data and your friends’ data gets complicated. The aforementioned FTC order specifies that affirmative express consent is not required for sharing of nonpublic user data to which another user has authorized access, as long as “such sharing does not materially exceed the restrictions imposed by a user’s privacy settings”. This last part is key, as it is debatable whether Facebook’s notifications regarding changes in privacy settings, and Facebook’s privacy setting instructions, constitute informed consent. Default API access to all of a Facebook user’s friends’ data has been deprecated since 2015, but default privacy settings for Facebook users are still set to share some data with a friend’s apps. Users have to jump through significant hurdles to switch settings to not share their data with their Facebook friends’ apps — one recent article says it can take 27 clicks.

TL;DR

There are no easy ways to define informed consent, but that hasn’t stopped many people from trying. One grassroots effort, amusingly called “Terms of Service; Didn’t Read,” is to distill terms of service into a simple grade, “A” through “E.” A badge on websites spares users the cognitive burden of comprehending every legal detail of a written policy, while browser plug-ins could let users set their preferences automatically, thereby stopping the user from visiting any website with a grade “C” or lower, for example. This sounds like a great idea, but widespread acceptance is a long way off, not to mention the considerable public education effort that would be required.

While “informed consent” may be as nebulous as ever for social networks, it is clearer in the world of energy data. States where energy data may be shared by consumers with third parties have determined consent processes and specific language that must be presented to consumers. For example, the Illinois Commerce Commission has created a standardized form for data-sharing to which customers must consent. The form was deliberately designed to fit on a single page and succinctly describe the transaction for the customer.

While some technical details are absent from Illinois’s regulation -- for example, it’s unclear how the form should be presented differently on mobile devices -- it is refreshingly specific. Both utilities and energy management companies in Illinois are grateful for a “safe harbor” consent process that reduces legal uncertainty. With regard to informed consent, specificity is something to which public policy should continually strive. Given Facebook’s recent troubles, Mark Zuckerberg no doubt wishes he could trade the courts’ unpredictability for a public utility commission’s clear set of rules.